The small hosting the small in Antarctica

Submitted by editor on 26 January 2026.

Figure 1. Photo of the springtail Cryptopygus antarcticus moving across a lichen (likely Xanthoria spp). Photo taken by Stef Bokhorst.

When people think of Antarctica, they usually picture penguins, seals, and a lot of ice. But in the tiny ice-free areas, carpets of mosses, lichens, and algae form miniature forests. These patches host Antarctica’s terrestrial animals: billions of mites and springtails (Fig. 1).

From earlier studies, we already knew that nitrogen plays an important role for these animals. But we didn’t know whether its effects differed between vegetation types, between mites and springtails, or how moisture content might shape their distributions, and if the effects of moisture and nitrogen change across the maritime Antarctic. In short: we lacked a clear picture of what determines where these animals live, and why. To find out, our team combined counts of mites and springtails from Antarctic vegetation samples collected over more than a decade (2013–2024) across the maritime Antarctic (Signy Island, Byers Peninsula and Rothera) (Fig. 2–4). In total we extracted and identified 240 000 individual microarthropods from vegetation for this study.

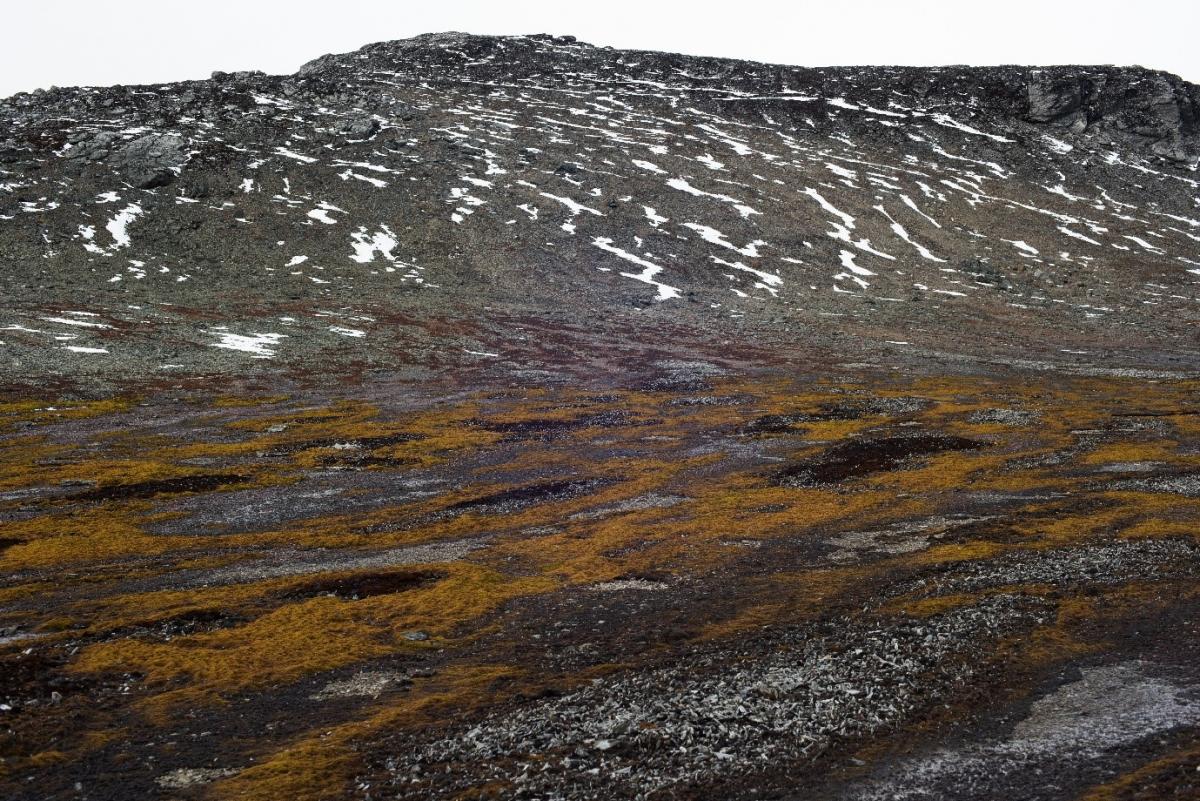

Figure 2. A photo of the ‘Backslope’ near the British Antarctic Survey’s Signy Research Station, with a mixture of moss and lichen vegetation. Photo taken by Peter Convey.

Figure 3. Photo of a mosaic of moss-dominated and lichen-dominated habitats on Signy Island.

We found that not all microarthropods are found everywhere, springtails prefer mosses and algae, while mites don’t show a clear preference. More importantly, vegetation characteristics explained their abundance. Nitrogen content consistently increased arthropod abundance, and water content almost always increased springtail abundance, but sometimes negatively impacted mite abundance. The relative importance of moisture and nitrogen content shifted with geographic location: moisture was most important in the harsher, drier south, while nitrogen mattered more in the milder, northern regions. Vegetation type and traits thus together determine the small-scale habitat for microarthropods and it is not just climate that determines their distributions.

This matters because Antarctica’s terrestrial environment is changing. With climate change, ice-free areas are expanding, but human activity is also increasing and vascular plants are expanding. Understanding which habitats support which species thus becomes increasingly important if we want to protect these species. To get a first estimate of how many mites and springtails might occur across the maritime Antarctic, we combined our data with the first satellite-based vegetation map of Antarctica (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-024-01492-4). For more precise estimates, we need to know more about the traits of specific vegetation types and work with aerial imagery that can better distinguish species within vegetation or even detect moisture status or nitrogen content (or distance to marine vertebrate colonies, as that is a strong determinant of nitrogen content in Antarctic vegetation).

Figure 4. Photo of a wet valley with extensive moss carpets on Lagoon Island near Rothera Station (British Antarctic Survey).

This kind of study could only be written after multiple expeditions to Antarctica. I spent about five months in total across two Antarctic field campaigns in 2023 and 2024 to add more data to the dataset we already had. On Signy Island, collecting samples meant carrying backpacks full of moss and lichen samples across the island and sometimes even over its small icecap. At the end of the day, those backpacks felt absurdly heavy for something that would yield just a few millimetres of arthropod life under the microscope. The result is one of the most detailed datasets to date linking Antarctic vegetation traits to arthropod communities. This provides a baseline for tracking how biodiversity in ice-free areas is responding to warming and human disturbance. Knowing where these tiny animals live, and which habitats (Fig. 5) sustain them, is a first step toward better protecting Antarctica’s terrestrial biodiversity.

Figure 5 Photo of a variety of lichen species with Usnea antarctica in the foreground.